For Whom Bell Toils: Medical Imaging by

Telephone

Ellen R. Kuhfeld, PhD

In the War Between the States, being shot was merely the start of your

troubles. The surgeons then had to find and remove the bullet. If it were

comparatively near the entrance wound, doctors could probe with their finger.

This was sensitive, and caused less damage than mechanical probes.

If the bullet were further in, a metal probe had to be inserted into the

wound as gently as possible, to improve odds of its following the path of the

bullet rather than forcing its own way through the flesh. To tell the difference

between bullet and bone, Nelaton's probe had a porcelain tip which would abrade

a dark streak from lead. Then a long, thin bullet forceps could be inserted in

the wound to grasp and remove the object found by the probe.

Fortunately for the wounded, the 1860s also saw the massive use of surgical

anesthesia, and early experiments in injected morphine analgesia.(1)

Even so, the Civil War hospital was not a welcoming place. My family history

mentions James Pulver, an ammunition-carrier whose face and hands were terribly

burnt by an explosion. His commanding officer told him to go to a hospital;

James said that people died in those hospitals. Going back to the lines was his

only other choice; he bandaged his hands, tied the reins to his saddle, and kept

working. He carried the scars to his grave, many years later.

Ironically, the conical "minie ball" projectile introduced during the Civil

War had a tendency to come to rest on the opposite side of the body from its

point of entrance. With some way of locating a metallic body directly, the

surgeons could have taken a shortcut with their scalpels instead of probing an

already-traumatized wound. (2)

But bullets are not the only disturbing form of metal. Alexander Graham Bell

invented the induction balance to cancel out line interference on his telephone.

During development, he noticed that they could easily be driven out of balance

by a nearby piece of metal.

On July 2, 1881, the assassin Guiteau shot President Garfield. One bullet,

especially, worried physicians; but they were afraid to probe the wound in the

critically-weakened Chief Executive. Perhaps an induction balance could be used

to find the bullet in Garfield's body, so surgeons could remove it? (3)

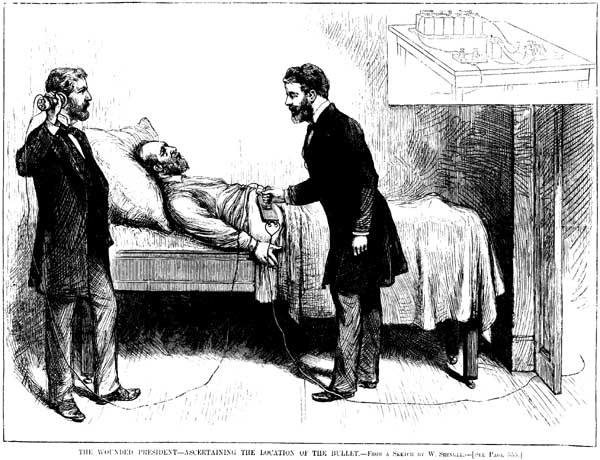

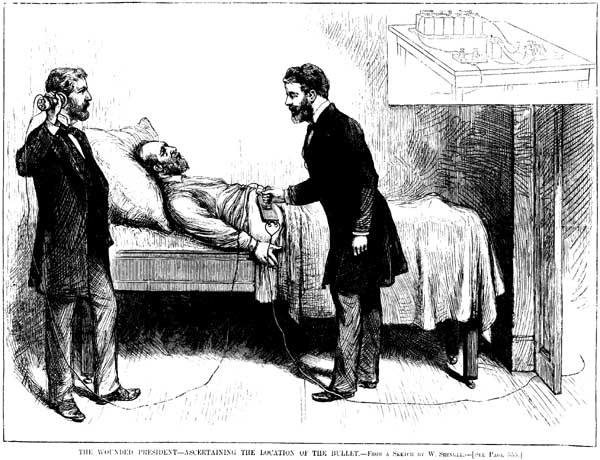

Bell and his associate Sumner Tainter immediately came to Washington and

began experiments to refine the induction balance. The first trial with Garfield

was a failure; the second, reported in Harper's Weekly for August 13, 1881, was

considerably more promising. To quote the article in full:

Searching For The Bullet

The experiments made by Professor Alexander Graham Bell with the view of

determining by the aid of the electric current the location of the bullet in

the President's person were of the most interesting nature. The possibility

that a time might come when it would be necessary to make incisions at once

for the removal of the bullet, without consuming precious time for further

consultation, gave to the experiments an importance which added greatly to

their interests.

An apparatus known as the induction balance had been used by Professor

Bell in analyzing metals. This instrument, modified so as to impart to it the

highest degree of sensitiveness, was used in the search for the leaden ball.

Its nature is such that it is not easily understood except by electricians. It

consists of a battery, two coils of insulated wire, a circuit-breaker, and a

telephone. The ends of the primary coil are connected with a battery, and

those of the secondary coil are fastened to the posts of the telephone. This

latter connection renders audible any faint sound produced by the

circuit-breaker, or any change in the pitch of that sound. The coils may be so

placed in their relationship to each other that no sound is made by the

circuit-breaker. They are then said to be balanced, and the wires are

extremely sensitive to the disturbing presence of any other piece of metal. A

bullet like that with which the President was shot, before it was flattened,

will, when placed within two and one-half inches of the most sensitive point

on the pair of coils, cause a faint protest against the disturbance to arise

in the telephone. A flattened bullet of the same bulk, when presented with its

flat surface toward the coils, will make its presence felt at a distance of

nearly five inches. When its sharp edge is turned toward the plane of the

coils, no sound is produced beyond the distance of one inch.

With these facts in view, the experiments to locate the position of the

bullet in the President's body were begun. The patient was bolstered up in

bed, and he watched the proceedings with mute interest. His physicians stood

around. Professor Bell stood with his back toward the President, holding the

telephone to his ear, while Mr. Tainton, Professor Bell's assistant, moved the

coils over that portion of the abdomen where the leaden ball was thought to be

imbedded. When the sensitive centre of the instrument was immediately over the

black and blue spot that appeared shortly after the President was wounded,

Professor Bell said, "Stop! there it is."

The experiment was repeated several times -- once with Mrs. Garfield

listening at the telephone; and she told the President when the coils had been

brought to the spot where the presence of the bullet had previously caused the

delicate instrument to give forth a singing sound. From these tests it was

inferred that in any event the bullet was less than five inches from the

surface, and that if it was only slightly flattened, or if its edge was turned

obliquely toward the surface, it might be much nearer to the skin. The

conclusion reached was that if it should become necessary to remove the bullet

at any time, this might be speedily accomplished by two quick cuts with the

surgeon's lancet.

The prime rule of medicine is "first, do no harm". Like all rules, it is

easier to obey when one has both incentive and time. With a thousand wounded

soldiers after the battle, doctors did what they had to do to save lives. The

Sanitary Commission's report of 1861 noted that "In army practice, attempts to

save a limb which might be perfectly successful in civil life, cannot be made.

... [they] will be followed by extreme local and constitutional disturbance.

Conservative surgery is here in error; in order to save life, the limb must be

sacrificed." (4)

Ah, but a wounded President clinging to life for eighty days, surrounded by a

throng of argumentative doctors and inquisitive reporters! Seldom has there been

better incentive to develop new techniques for finding bullets accurately and

gently. Bell and Tainter worked furiously in the heat of a Washington summer,

improving their apparatus. The trials on Garfield were ultimately unsuccessful

(news reports were tilted towards official optimism, then as now). But Bell

continued development, and by October successfully demonstrated his detector on

veterans who still bore bullets within their persons. (5)

In 1896 the X-ray came along. Its first surgical use, in February of that

year, was to find buckshot in a hand. (6) As we gained experience with X-rays,

we soon found that they were not so harmless as we hoped. And today, when

possible, we again use magnetic imaging instead of X-ray imaging.

References

1. Dammann, Gordon: Pictorial Encyclopedia of Civil War Medical

Instruments and Equipment, Vol. I (Missoula, Montana, 1989)

2. Dammann,

op cit pg 4

3. Mackenzie, Catherine: Alexander Graham Bell

(Cambridge, Mass. 1928)

4. Dammann, op cit pg 1

5. Mackenzie, op cit pp

238-241

6. Grigg, E.R.N., The Trail of the Invisible Light

(Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1965) pg 30

Harper's Weekly,

August 13, 1881

Home